Pedro Costa’s most recent movie, Vitalina Varela (2019), begins with a slow procession of a funeral cortège that emerges from the almost total darkness of an alleyway bordering a cemetery wall. The priest, whether from exhaustion or the tremors that constantly shake his hands, is shown collapsed on the sidewalk. The audience, like Vitalina, has arrived too late to see the funeral service, and the priest’s exhaustion provokes the question how many dead have been buried in this dark night. In a recent interview with Film Comment, Costa himself describes the lives of those who are the subjects of his Cape Verdean movies as condemned long before they were born. But Costa’s Cape Verdean films are not simplified allegories of colonial violence or of damaged life in relation to this superhuman inheritance. There is nothing so abstract or diagnostic in these movies, and Vitalina Varela (‘VV’), in particular, represents a crowning achievement of this series not only because it takes up the perspective of a woman as exemplary as Mrs. Varela, but, uniquely in this series, VV celebrates the autonomy of its protagonist. But to see this autonomy rightly, we will need to contrast this against the primarily male dynamic of the earlier films in this series that begins with Casa de Lava (1994), and re-commences in the third film of his Cartas de Fontainhas trilogy, Juventude em Marcha [Colossal Youth] (2006), the short film Tarrafal (2007), and the precursor to VV, Cavalo Dinheiro [Horse Money] (2014) in which Mrs. Varela made her debut as herself.

VV wrests the narrative center of this series of films away from Ventura, who, as far as I know, never quite plays himself as such in the way that Mrs. Varela extensively portrays herself, and who is a constant appealing and enigmatic presence in the series from Juventude em Marcha through VV. It might be the specific biographical subtext of VV that shapes the film towards thinking of it as representing an achievement, and that consequently presents the other films in this visually and narratively stunning series as hopelessly trafficking in ghosts. But Costa’s movie is no documentary, though it contains correspondences with the experiences of Mrs. Varela, and it presents visually stunning moments that span beyond her narrative and connect VV with the earlier films. Costa’s movies in this series and beyond it (thinking primarily of Ossos [1997] and No Quarto da Vanda [2000]) are thought to achieve the status of testimonies. Indeed, the trilogy of Fontainhas films have been described as “tell[ing] us forcefully that it is up to art to cast in relief the world that has been lost.”[1]

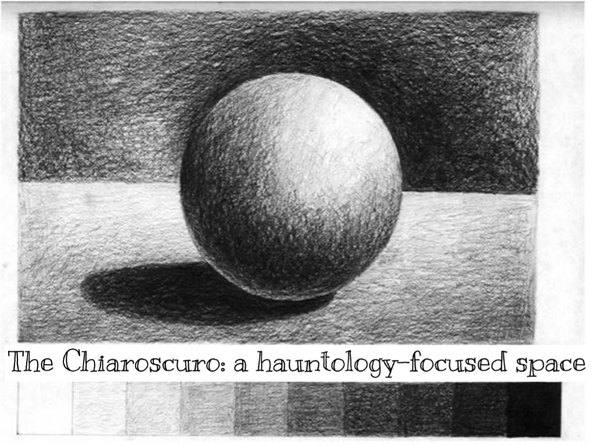

Within this testimonial, melancholic, and perhaps condemned environment, it is implausible to expect a depiction of meaningful routes for agency. Jacques Rancière, in his discussion of “The Politics of Pedro Costa,” describes the subjects of Costa’s films as destined to be marginalized. This fate of marginalization pushes the films into a kind of grim aestheticism (of which Rancière is understandably wary), meaning that the films, viewed from this angle, might be thought to be merely ornamenting or embellishing scenes of human misery by framing them (in Rancière’s words) in “a chiaroscuro of the Dutch Golden Age.”[2] While Costa’s films are, generally, visually stunning, they do more than make a claim about the relation of art to the dispossessed. Indeed, to frame an analysis in these terms is to nullify the agency of the subjects of Costa’s films, or to regard their actions or interests as only the outer attenuating ripples of an anterior colonial impact. Against this victimized framework, Costa’s movies are deeply concerned with the representation of lives, the concerns that are made significant and the nature of this significance itself, that are set in the routines and networks unfolding from a complex colonial inheritance. To begin from the generalized condemnation or fatedness of Costa’s subjects is to avoid noticing the ways in which they are constantly negotiating attempting to come to terms with a past or a future.

Avenues of Hauntology

Orthogonally to Rancière’s treatment, I propose that it is of paramount importance to think about VV through the lens of the concept of hauntology. In many ways, as we will see below, thinking of VV along this axis helps us appreciate it as a turning away from the melancholic or temporally dislocated repetitions of the predominantly male characters in Costa’s previous films. It is this paper’s claim that hauntology is the proper lens for understanding how VV’s difference from the logic of a beautifully framed victimization by distant (in terms of both a wider scale and in the sense of being historically far in the past) and colonially centrifugal forces that, per Rancière, are exhibited in Costa’s earlier films. Towards the end of this paper I claim that VV’s singularity here can be glimpsed in the change from melancholia to mourning, and I shall say something about that connection (between responses to hauntology, melancholy, and mourning) here.

The punning portmanteau, ‘hauntology,’ first emerged in Derrida[3] and has been a central concept in the popular critical work of Mark Fisher.[4] The use of the concept by both Derrida and Fisher is rooted in what might be called the equally ethical and socio-political demand to locate or identify lost possibilities and to consider what the pursuit of these might mean. In Derrida, this term spun out of his engagement with a reading of ghost scenes in Hamlet as a frame for thinking about the specter that Marx and Engels announced was haunting Europe. And while, in 1994 at least (if not more so today), some of the scholarly world was captivated by Western Liberal Democracy viewed through the lens of Fukuyama (1992) as having accomplished the End of History, Derrida’s approach engages with this notion of the telos of history but his primary concern lies elsewhere.

In the introductory “Exordium” to Specters of Marx, Derrida makes it plain that one of the central concerns of his use of the idea of ‘hauntology’ is not, primarily, to speculate about the fate of communism or the putative End of History but instead his initial purpose is to consider the lines with which the presence of vanished possibilities informs the expression of the ethical desire to learn, at last, how to live. In many ways this Derridean line bears immensely on the unfolding of VV, since this “heterodidactics between life and death” as “ethics itself: to learn to live — alone, from oneself, by oneself”[5] is essentially what Vitalina Varela herself learns through VV, hemmed-in by lost possibilities and even by ghosts. The place of this hauntological-ethical tutelage in VV presents a way of stepping aside from the wreckage of victimization that occupies Rancière’s discussion of Costa’s earlier films. The discussion at the beginning of the next section regarding the constant emphasis that there is nothing in Lisbon for Vitalina underscores the way that her project, the central arc of the film, is not constrained by actually existing conditions. As Derrida remarks: “The time of the ‘learning to live,’ a time without tutelary present, would amount to this...: to learn to live with ghosts, in the upkeep, the conversation, the company or companionship, in the commerce without commerce of ghosts. To live otherwise...more justly.”[6]

I take Derrida’s emphasis here on justice, and the idea of learning to live with ghosts, as a way of signaling the transformative work of mourning (in contrast to what I will call a kind of melancholic life at the mercy or behest of lost possibilities). But before discussing Fisher’s approach, which I think bears more resemblances to the melancholic life that reflects upon these ghosts (and so, to many of the men in Costa’s series, represented later in this paper by Ventura), I wish to underline how this spectral dimension takes it form precisely in the situation of Vitalina Varela, where “[i]t is necessary to speak of the ghost, indeed to the ghost and with it, from the moment that no ethics, no politics, whether revolutionary or not, seems possible and thinkable....”[7] VV is a film that celebrates the accomplishment of Mrs. Varela, carried out across years and a vast ocean, carried out in the loss of her husband, carried out precisely with these absences fully present to her and as conspicuously missing for the film’s audience, and, in Derrida’s framework, VV becomes a film about justice: “this justice carries life beyond present life or its actual being-there, its empirical or ontological actuality: not toward death but toward a living-on [sur-vie]... a survival whose possibility in advance comes to disjoin or dis-adjust the identity to itself of the living present....”[8] It is only through the dimension of what Derrida is outlining as justice (but which we might also describe as mourning, or perhaps more simply, if ambiguously, as love) that Vitalina’s living-on in her disjuncture with the present of Lisbon at which she arrives early in VV.

Costa’s films allow this ghostly presence to unfold in different ways. The series of Cape Verdean movies depicts two avenues for pursuing this disjoined temporal-historical condition. The first is one that I have already described as mourning, and that Derrida describes in the Exordium to Specters of Marx as a kind of justice. Briefly, this might be said to be the Hamlet condition, where one finds that the ‘time is out of joint’ and understands oneself as having a vocation to set it right. The Derridean-Varelian line understands the “non-contemporaneity with itself of the living present”[9] as a project, something to be worked through or reckoned with, as laden with personal responsibility even though (at least initially), as Vitalina is repeatedly told upon her arrival, there is nothing for her there, nothing for her to do, she is too late. That from which her obligation emanates is precisely not given objectively; her responsibility is sourced from beyond the living present.

The second avenue is shaped by the hauntology outlined by Mark Fisher to describe the melancholy resulting from the disappearance of projected futures.[10] Fisher’s use of the notion as a tool for cultural analysis is indebted not only to Derrida but also to Franco Berardi as, particularly, the “cancellation of the future.”[11] Fisher is keen to distinguish hauntology from the familiar nostalgia for the past, but he accepts that there is at least a “formal nostalgia” or a longing for “processes” that had at least been announced (even if through thick ideological lenses) for greater democratization or pluralism in local or global communities.[12] For Fisher, these terms are no longer credible even as red herrings, unable to function as a bait for popular credulity, and his concern with hauntology focuses exactly on this as having been lost: “What should haunt us is not the no longer of actual existing social democracy, but the not yet of the futures that popular modernism trained us to expect, but which never materialised.”[13]

Hauntology, in Fisher’s hands, resembles nostalgia (but, we might say, for lost futures, not for the receding past), and he readily associates it with a “failed mourning”[14] which consists “in a refusal to adjust to what current conditions call ‘reality’ — even if the cost of that refusal is that you feel like an outcast in your own time.”[15] We will see examples of this mode of failed mourning and being outcast in one’s own time through several of the male characters from Costa’s Cape Verdean films.

There are, thus, important differences between Derrida and Fisher on the subject of hauntology. Their accounts differ with respect to the relative weight given to the sense of possibility, and which direction of temporality informs the spectral directive. In Fisher and in several of the male characters in Costa’s films, the failure of the future becomes a spiritual cessation and compulsion to repeat outmoded cultural forms. Also, in Fisher and in many of the male characters of Costa’s series about the lives of Cape Verdeans in the orbit of Lisbon, the liberating key would be an objective correlate to unlock and grant significance to erstwhile repetitive meandering. For Fisher, importantly, there is a sense that what goes by the name of the twenty-first century must have the “feel” of the future, of having advanced on the nineties in some way to dispel the sense of pointless belatedness.[16]

But Derrida’s Exordium makes it clear that his understanding of hauntology is not the result of an external failure as such, but, rather, is a common aspect of all ethical concern. Or, at least, it need not be the sort of messianic failure that Fisher’s approach laments. The basic normative concept of ‘justice’ requires, in Derrida, a proximate understanding that one is acting in fealty towards both the living and those who are not present (either dead or not yet alive). These non-presences are invoked by any ethical or political concern worthy of its name; even the case of learning how to live, by oneself, finally, requires a one-sided commerce without exchange or socius without understanding. In Derrida’s formulations: no ethics, no justice, no responsibility is possible that “does not recognize in its principle the respect for those others who are no longer or for those who are not yet there.”[17] And Derrida’s conception of justice, one might say, is so absolute that it includes a necessarily open-ended conception of those others (as past or potential future victims) to whom one owes consideration even though they are not at all present to one’s immediate concerns. Derrida describes this concern as secretly unhinging the present,[18] and so maps onto the phenomenal feel of Fisher’s melancholic haunting as producing a sense of being “outcast” in one’s own time. It is important to recall here that the cause of this unhinging is always a notable absence, a chain linked through something essentially not present (or conspicuously absent in any materialist or objective sense). But it is equally important to be aware of the different responses, different modes of response, to this absence: the Derridean line, here associated with Vitalina Varela herself, which pursues the mourning work of loving adjustment, committed by an absolute claim evidenced in a telling remark of hers captured by the title of this paper, and a melancholic line, associated with Fisher’s reading and many of the male characters of the series of Costa’s films under discussion here.

Having briefly outlined the uses made of this enigmatic term, I will now describe these different hauntologies through the lenses of Costa’s Cape Verdean films. The films themselves allow us to situate both avenues of approach to the idea of hauntology, and they body forth the different modes of response just mentioned in ways that both clarify the distinction between the two avenues for understanding the uses of hauntology but also help clarify the ways that the films themselves can usefully be understood to be more than merely the gorgeously ornamented memorial testaments to victims as they might otherwise be taken to be.

There is Nothing for You Here: Mnemonic Traces and Layers

VV begins with a funerary procession away from a burial, and offers the audience a glimpse into some of the routines of postmortem arrangements. It seems exactly pertinent to wonder how many have been buried along with Joaquim (Vitalina’s husband). Vitalina is told upon her arrival that she has arrived too late, her husband has already been buried three days before, and that there is nothing there for her. But was there ever anything for Vitalina Varela in Lisbon? When would her arrival have been timely? The ways in which anything could actually have been said to be there for her are each revealed to have been betrayed or buried some three days before. Her refusal to leave things that way, as betrayed and buried, as nothing, is a refusal to come to that sort of passive agreement with fate, to have things, generally, given for her. Her insistence to construct a home for herself, against the passive reception of the nothing offered to her, is what the film celebrates and places VV in a different category than those earlier members of this series presided over, one might say, by Ventura’s melancholy and collapsing priest.

Costa’s interiors are often compared with Dutch Baroque-style paintings (see Rancière’s mention above), accompanied by noting the quality of light in the depths of the secular world, but his shots in streets, or even in the passageways between the staggering constructions that house the lives he lingers with, are nothing if not members of the metaphysical spaces painted by Griorgio de Chirico. The vertiginous structures — which Pedro Costa’s mastery of close spaces renders as the cells of ascetics or prisoners, as kin to Liebskind’s Garten des Exils, and as the stifling slums of Kafka’s places of justice — inhabited by Costa’s human subjects challenge the belief that the time has ever been right for them to receive or house human lives. Human lives and their habitations all seem to be persisting in ways that defy gravity. “There is nothing for you here:” this statement could be sent to any of the characters of Costa’s movies and be received as a personal truth. Except for Vitalina. Centering the film on Vitalina emphasizes the differences in experience between the men and the women who have been part of the circuit of labor travelling to Lisbon and then sending or failing to send back to Cape Verde for their past commitments, completing a project of attaining a future desired at one point, and, among the presences of Costa’s Cape Verdean series, only Vitalina, is on the way to completing this loop from the past to the present. Vitalina’s resolve for the past to matter, for a past that can meaningfully be her own, to be recognizable or claimable as hers, sets her apart from the men of these movies.

As a member of the series of Costa’s films about Cape Verdeans in relation to Lisbon, VV gathers elements of light and darkness that stylize Costa’s earlier films in this series, it gathers bodies present in mute petition for something unknown and which cannot be offered within their present world, it channels the flow of ghosts from temporally or geographically distant pasts of the earlier films, but yet it breaks from the earlier films of the Cape Verdean series by offering something other than a damnation to (in a phrase from the predecessor to VV, Cavalo Dinheiro) “lay with the dead, locked in silence.” Vitalina offers meals to the men who are frequently in her home to apparently mourn Joaquim, but who remain as impedimenta, sitting or standing in silent non-petition, but it is her meals that evoke for them the idea of a home. And, importantly for my purposes here, she offers advice, an authoritative reminder, to a homeless young man, Ntoni, who is not sure if things will work out with his partner Marina. Vitalina advises him “if it’s love, it must work out.” This immediate confidence in the effort of love to find a way — a confidence which in her case has been tested and perhaps fortified by the betrayals and neglect she has experienced — singles her out as bearing a faith that is of an entirely different order than that of Ventura’s melancholic priest.

As much as the structures housing the lives of the persons in the opening of VV disorient the audience, just so the language and, at times, the lives of the characters in the series appear governed only by an oneiric disorder. Towards the beginning of Cavalo Dinheiro, Ventura is visited by four figures from his past, (Lento, Ventura’s pupil in Juventude em Marcha, reduced to medicinally-administered tranquility; Benvindo, who has fallen from the third floor in a factory accident; a silent man who has destroyed his good job, potentially murdered his family, and destroyed his house in an act of arson; an unintroduced apparition of Joaquim, later identified in Cavalo as the husband of Vitalina, who bears most of the narrative of this sequence; and yet another silent and unintroduced compatriot in the background). Joaquim, who has already declared that he and Ventura are bound in life and death, continues his explanation of the various traumas suffered by those visiting Ventura by announcing that the military police, who apparently run the hospital where they are kept, can do nothing to them all, and he justifies this response by announcing the logic governing their experiences:

Our life will still be hard. We’ll keep on falling from the third floor. We’ll keep on being severed by the factory machines. Our head and lungs will still hurt the same. We’ll be burned. We’ll go crazy. It’s all the mold in the walls of our houses. We always lived and died this way. This is our sickness.

This prophecy wends its way into the following moments of Cavalo Dinheiro when, in response to a doctor’s question of whether whatever befell Ventura will happen again, Ventura responds that it certainly will, and then, in response to the doctor’s question whether Ventura can describe what happened to him, he merely replies “It’s because of the mold in our walls.” This coyness in response functions as a code that eludes the official or medical registry and is intelligible as a response to the question only through the memory of the film’s audience. But if the audience is meant to understand itself as being on the ‘inside’ of a joke at the expense of the official record, the audience is quickly shoved out of this position of privilege by the response to a question a few moments later: (Doctor:) “Do you sleep well? Do you wake up in the middle of the night?” (Ventura:) “A big black bird landed on my roof.”

From these exchanges alone, the audience must acknowledge that so much of the language spoken may potentially be encoded and that the criteria for understanding what is said by the characters of Costa’s movies may not always be immediately shared with or given to the audience. Even when the big black bird returns late in Cavalo Dinheiro in a harrowing scene of Ventura being tormented by his past, shut in an elevator with a metallic soldier who demonically harasses Ventura at the end of his life (“You have no destiny nor horizon. You are and have nothing”) with a repository of past moments that Ventura would as sooner neglect and an unwelcome anti-prophet, (“This is the story of young life, of life yet to come and of all things to follow”) foretelling a “day [that] will come when we accept our suffering. There will be no more fear nor mystery.” The big black bird, like other moments of this exchange, appears only as a private historical object, a condensed ledger or symbol whose full measure is withheld from the audience’s grasp. By contrast, the essentially open audience for Vitalina’s reminder about the imperatives and obligations of love, its basis in an uncoded understanding of fundamental meaning, already speaking a kind of higher language that relies on the full significance of what is meant when certain things are said or promised, pushes her into a unique place in these films.

Figures 1 and 2: De Chirico's Apparizione della ciminiera (1917) and Ventura in a scene from Colossal Youth.

Almost everyone else in this series is, in some manner, unconnected to the films’ present. In response to the doctor’s question (in Cavalo Dinheiro) whether Ventura knows what day it is, he responds “Eleventh of March, 1975.” That date might have been recognized by the doctor, and may be understood by those audience members familiar with the details of Portuguese history as the commencement of an attempted coup against the populist government that had been set up nearly one year beforehand, which ended what was called the Estado Novo. The Estado Novo (1926-1974) was known chiefly by its repressive, costly, and unsuccessful campaign in Portugal’s colonies in Africa, and the liberating period (the “Carnation Revolution”) that displaced the Estado Novo was briefly threatened by an attempted and drastically insufficient right-wing coup on the eleventh of March 1975. In claiming that his present is that day, and then claiming that the current president of Portugal “must be that General Spínola” (i.e., the perceived mastermind of the attempted coup against the new left government), what appears to the audience ignorant of these events as Ventura’s madness is in fact yet another kind of coding.[19] To remain at the date of the attempted coup of March 11, 1975 is to be disconnected from the revolution’s first fruits: the independence of the African colonies (including Ventura’s native Cape Verde, on July 5, 1975, only a few months later). Essentially, the date of Ventura’s present moment is a date when the liberating movements away from the period of Estado Novo are in peril, and his supposition that the president must be General Spínola is to claim, in code, that his moment is a time when he is still a colonized subject.

The supremacy of this unhinged and magical temporality, unseen or barely heard provocations, entire scenes of being possessed by a vanished past (e.g., in Cavalo, Ventura paces about the ruins of the old building company, making a call on a smashed telephone to receive an order, and he encounters Benvindo who is awaiting his salary as if for Godot) is but one manner in which historical forces seem to have robbed Costa’s characters of their agency, and where their interests or attention cannot be located in what is visually present to them or the audience. I say ‘seem’ because, the inexorable mystery of these films is how anyone moves at all, how anyone is able to go on in the construction of a house, in the upkeep of a ruined church, in the least routine; because Costa’s characters do go on, with cherished private objects and circuits of commerce with each other and their environs, in ways that make Beckett’s characters seem privileged to be, say, more demonic than phantasmic. The films’ moment is not a space in which these characters can meaningfully act, rather these lives are administered ones, whether by hospital/prison staff, by a real estate agent, or by coded beacons that haphazardly light up from the past in conversation. Thus, Ventura characteristically reminisces (as the character ‘Ventura’ of Juventude em Marcha or the character ‘Ventura’ in Cavalo Dinheiro), and, for similar reasons, this is why Vitalina almost introduces herself to the audience of Cavalo Dinheiro by naming the past date which still lingers over her life (a date she only knows from official letters she received about the death and burial of her husband).

The entangling of the past in Cavalo Dinheiro’s present is not to suggest that Ventura is fully attentive or responsive to what might be thought of as his biographical past. Vitalina, less intensively than the demon soldier who later traps Ventura in the elevator, casually reminds him of Zulmira, his wife in Cape Verde, to which he responds by confessing that he already has had the money to send her a ticket. He then begins to take a cursory or nostalgic interest in other neglected things of his past in conversation with Vitalina, his house (of which Vitalina tells him “not a stone is left standing”), his pigs and goats (“all ran away”), his donkey, Fogo Serra (“dead”), and his horse [i.e., cavalo], Dinheiro (“The vultures tore him to pieces”). The very title of the film, Cavalo Dinheiro, is revealed to be one of these private codes, a transfigured subject of neglect, a forgotten creature abandoned and long-dead, which had only been preserved in a phantom possibility of life by being buried under years of silence.

**This is the first segment of the article; continue to the next section. The endnotes can also be found at the end of the latter section.

No comments:

Post a Comment