Philosophically questioning the relation between life and death is usually considered to be the proper territory of movements such as existentialism and Lebensphilosophie. This belief is instigated by the explicit treatment of the life-death relation by authors such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger and Sartre who, each in their own way, exposed and examined the presence of death in our daily lives. With the rise of poststructuralism – undermining the existentialist ideal of a free and autonomous individual – subjects such as life and death also lose their central importance, as they are replaced with historical, linguistic, and textual concerns. Or so one thinks, because the case of Jacques Derrida provides us with a vivid counterexample in this regard.

Over the past decades, various scholars have demonstrated how questions pertaining to life and death are the driving force of Derrida’s philosophy, which is often referred to as deconstruction. Four of these authors are examined in this survey article. The first is Geoffrey Bennington, a renowned Derrida-scholar, who sparked interest in this theme with a conference-paper called ‘‘That’s Life, Death.’’ The second author is Colin Davis, who, in Haunted Subjects, draws on literary theory, psychoanalysis and deconstruction to uncover the various ways in which the living are haunted by the dead. Yet, Martin Hägglund was the first to systematically assess Derrida’s rethinking of life and death, as part of his effort to capture the logic of deconstruction in his book Radical Atheism. Most recently, Robert Trumbull has joined the conversation with From Life to Survival, which studies the revised concept of life that emerges from Derrida’s engagements with Freud.

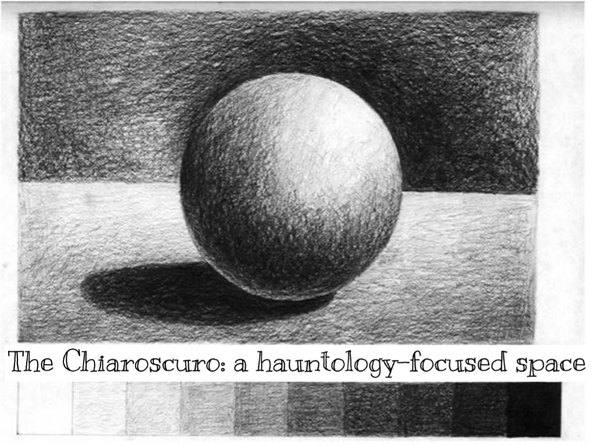

Although each of these works appears as a comprehensive account of the deconstruction of life and death outlined in the work of Derrida, a mutual comparison will reveal their distinctive limitations in this regard. Only when taken together, they are able to indicate what a new ontology, anthropology and ethics of life-death might look like. Hauntology is the term Derrida himself used to capture the insight that death always haunts life and vice versa. The aim of this survey article is to map the various guises of this hauntology.

A New Ontology of Life

Bennington, Hägglund and Trumbull have all studied the new ontology of life that can be found throughout Derrida’s oeuvre. This new ontology is the product of applying the logic of deconstruction to the traditional opposition between life and death. Hägglund captures this deconstructive logic in the following formula: ‘What makes X possible is at the same time what makes it impossible for X to be in itself.’ (25) In his Radical Atheism, it is the constitution of time which functions as this condition of (im)possibility: starting from Derrida’s idea that the living present is actually never fully present to itself, because it is haunted by both the past and the future, Hägglund opposes ‘the philosophical logic of identity’, which holds that ‘what is must be identical to itself’ (14). Trumbull describes the central insight of deconstruction in a similar fashion, emphasizing that inescapably, there is some form of heterogeneity or otherness inscribed in what we usually believe to be fully self-enclosed, whether this is the present, speech, philosophy or something else.

The central concern for all three authors, however, is to illuminate how this logic plays out in the case of life. What makes life possible, they argue with Derrida, is at the same time what makes it impossible for life to be identical to itself. Drawing on Derrida’s own description of life as necessarily engaged in an exchange with death, they reveal how the human organism, for example, is constantly trying to avoid a state of absolute life, just as much as absolute death, thus never residing with the one or the other. This gives rise to the non-oppositional ontology of life as life death, which is hinted at by Bennington, systematically treated by Hägglund, and chronologically reconstructed by Trumbull.

Although each of these scholars engages with Derrida’s deconstruction of life and death, their reasons for doing so diverge. Whereas Bennington just seeks to instigate discussion by citing a series of ‘magnificent’ quotes from Derrida’s work (49, 61n3), Hägglund tries to develop a ‘logic of radical atheism’ that would free us of our religious ‘desire for God and immortality’ (1). Transcending our mortal existence in the form of a life after death, Hägglund argues with Derrida, is actually not desirable, because immortality annihilates those characteristics of time which are the condition of possibility for things to happen.

‘If to be alive is to be mortal’, he writes, ‘it follows that to not be mortal – to be immortal – is to be dead.’ (8) For Hägglund, the alternative to this absurd desire for immortality is an affirmation of Derrida’s ontology of life as radically mortal and intrinsically divided. Even though this means that life will always be threatened by death, it is also the only way in which we can survive, or live on at all. Or as Bennington suggests: only this notion of life would be ‘a life worthy of its name.’ (59) Finally, Trumbull employs the thought of life as survival to make a case for the ethical and political implications of deconstruction, in so far as it enables us to critique the theological foundations of ‘our inherited political concepts’ (127).

Haunted Subjects: Deconstruction and Psychoanalysis

However, it would be a huge mistake to reduce Derrida’s hauntological engagements to a matter of mere ontology. As is nicely illustrated by the title of Davis’ book, it is not just life as a metaphysical concept that is exposed to its other, but also our own subjectivity which is haunted by death. In order to disclose this philosophico-antropological feature of the deconstruction of life versus death, both Davis and Trumbull have turned towards psychoanalysis, and the work of Freud in particular. ‘Freud’s controversial theory of the death drives’, for example, is taken up by both authors as it is a striking example of how, as Davis puts it, ‘death is re-located into the very centre of the living subject.’ (21) Freud famously postulated the existence of one or multiple (self)destruction-drives, and set them up against the life-drives as their opposing forces. The development of this theory is extensively discussed by Trumbull, and employed by Davis for analyzing films, which enables him to provide ‘a first sketch of the haunted subject’ (36), as torn apart between life-drives and death-drives that continuously oppose and relieve each other.

For Trumbull, however, the Freudian theory of the drives is only the starting point for showing how Derrida’s reading of Freud on this point gives rise to the idea of life death mentioned earlier, which indicates that exposure to destruction pertains not solely to human subjectivity, but to anything as such. It is at this point that Trumbull takes issue with Hägglund, who constructs this exposure to destruction primarily as openness to the future, which ‘makes everything susceptible to annihilation.’ (9) Against this view, Trumbull argues, first, that this idea of destructibility at the very heart of life could only be developed by ‘Derrida’s activation of the death drive’, and second, that this ‘exposure to radical destruction’ (8) forms a threat that is already present in the structure of life.

These joint but different mobilizations of the Freudian drives are illustrative for the way in which psychoanalysis and deconstruction are brought into dialogue with each other throughout Davis’ and Trumbull’s works more generally. Whilst Davis takes them to be ‘distinct but interrelated contributions to the ways in which we might think about death and the return of the dead’ (14) – the latter being the dominant subject of his book –, Trumbull is much more interested in the ways in which Derrida takes up psychoanalytic concepts for his own purposes throughout his career. As a consequence, psychoanalysis is presented as an invaluable source of inspiration for deconstruction by Trumbull, but often staged as a competing paradigm by Davis.

This is exemplified by Davis’ discussion of ghosts as they appear in psychoanalysis and deconstruction respectively. Whereas the former held that we should rid ourselves of the spectral presence of others in the crypts of the unconscious, as they are bound to mislead us, the latter called upon us to welcome the ghosts of both former and future generations into our world, since they remind us of our responsibility towards them. So in this sense, ‘deconstruction is about learning to live with ghosts’, Davis concludes here, while ‘psychoanalysis is about learning to live without them.’ (89)

One of the explicit aims of Trumbull’s book in turn, is to indicate how psychoanalysis is, in various ways, a condition of possibility for Derrida’s theorizing on life and death, up until his deconstruction of the death penalty in his latest writings. Like life and the living being, Trumbull remarks, ‘Freud’s discourse is divided, and there remains a dimension of Freud’s thought he himself does not think.’ (5) For Trumbull, the articulation of this unthought dimension has been one of the distinctive contributions of deconstruction, in the sense that it did not simply and uncritically adopt the Freudian inheritance, but rather ‘transformed’ or ‘rearticulated’ its concepts and ideas. What is ultimately revealed by psychoanalysis and deconstruction, however, both Davis and Trumbull agree, is that the subject is never identical to itself, for one thing because it is always already exposed to ghosts from the past and the future, and to its own death or destruction.

Mourning and Melancholia: An Ethics of Death

Postulating the existence of a drive for destruction is by no means the only way in which human subjectivity can be said to be haunted by death. All the authors discussed in this survey have drawn attention to the fact that Derrida’s philosophical reflections on these and related topics spring from a more personal engagement with his own life and death. Still, this existential motivation for the deconstruction of life and finitude is treated most extensively by Hägglund, who, by drawing on interviews and key autobiographical texts, paints a picture of a man that is continuously haunted by his own future death, and the death of others who were close to him.

Yet, if there is one thing Davis’ book demonstrates, it is that ‘death should not be an end’ (153), since subjects can survive, or live on by means of their spectral appearance in films, by means of their written heritage, and especially by means of those who are still living: all possibilities to which Derrida has devoted numerous impassioned analyses. Although this complex relation between death, mourning, writing and survival is briefly addressed by Hägglund, it is treated most extensively by Davis, who devotes a whole chapter to the way in which for Derrida, the subject is haunted by the death of others which it survives. By means of an analysis of Derrida’s collected memorial texts, Davis exposes the many paradoxes involved in trying to let ‘the dead survive in the discourse of the living’ (136) – a process in which the distinctions between self and other, fidelity and infidelity, living and death fade. ‘The dead others may survive only within us,’ Davis writes: ‘they live on only insofar as we preserve them, but they are no less other for that, they are that which is in us other than ourselves’ (138). As such, the surviving subject is touched by alterity: giving a voice to others within oneself creates a ‘fractured’ or ‘dispersed’ subject (142).

According to both Bennington and Davis, surviving after the death of others can be said to involve an ethics of mourning, or rather of melancholia: concepts that have often been contrasted since Freud’s theorizing on these subjects. Whilst Freud presented mourning as a temporary grieving process after the death of a loved one, from which one recovers by restoring the autonomy of the self, melancholia was seen as the pathological failure to ultimately rid oneself of the presence of the deceased other. In the writings of Derrida, however, thus Bennington remarks, ‘this melancholia is no longer seen as a pathological condition, and rather as a kind of ethics of death’ (xi). Indeed, Davis says, ‘Melancholia, here, is ripped away from pathology and transferred to ethics’, because keeping the other within oneself is presented as ‘the only proper relation to the dead other.’ (148) This, one might say, is exactly what Bennington has attempted to do in his Militantly Melancholic Essays in Memory of Jacques Derrida, that seek to keep Derrida alive after his own death.

Concluding remarks

This survey article has attempted to demonstrate that it would be a mistake to confine philosophically questioning life and death to the territory of existentialism and related movements. The collective efforts of the authors discussed have made us see not only how the opposition between life and death is ceaselessly deconstructed throughout the work of Derrida, but also how existential concerns instigate his deconstructive writings in the first place. The main upshot of this inquiry is that with Derrida, the opposition between life and death is transformed into the thought of life death as being inseparable. Indeed, if there is one thing the above analyses reveal, it is that life is never pure life, as it is haunted by death in a variety of ways, and that death is never quite death either, as the deceased live on by those who are willing to carry the death within themselves.

This hauntology of life and death, however, could only be grasped in its full scope by a mutual comparison of four major sources of Derrida-scholarship. If one would enter this field by reading Trumbull’s book From Life to Survival, for example, one might get the impression that Derrida’s theorizing on life and death pertains exclusively to ontology. Likewise, Davis’ Haunted Subjects provides us with a rich introduction to the ethical and anthropological aspects of deconstruction as it relates to the living and the (return of the) death, but forecloses its ontological dimension. Bennington’s conference paper, in turn, lacks systematicity, whereas Hagglund’s Radical Atheism lacks focus, as life-death is discussed as part of a much larger project. As such, it is only the combination of these studies which enables us to map all dimensions of Derrida’s hauntology of life and death.

A number of promising avenues for further research remain nonetheless, of which I shall mention three. First, it would be valuable to assess the consequences of hauntology for our understanding of authorship, by further investigating the relations between writing and survival. Has the insight that authorship entails living on by means of an uncertain exchange between the written inheritance and the favor of others been fully worked out? Hägglund has devoted a couple of pages to this topic, but a more comprehensive account seems warranted. Second, and related to this, it remains unclear what the survival of subjectivity in the form of writing entails for its interpreter, or, in other words, how the above hauntology relates to hermeneutics. If the return of the dead hinges in part on the inexhaustibility of their oeuvre, as Davis has argued with Derrida, then how should we conceive our responsibility as a reader or interpreter? Finally, it seems worthwhile to try to concretize all these rather abstract discussions into the form of a public philosophy product which is aimed at translating their most relevant insights back into the everyday existential domain from which they originally sprung.

Following a successful BA in business administration, Lucas shifted his focus to philosophy, completing both a BA and two MA programs in the field. His research explores the conflict between newly emergent subject-oriented and object-oriented theories of hermeneutic experience and their implications for the role and responsibilities of the interpreter. He specializes in contemporary continental philosophy, particularly the reception of Hans-Georg Gadamer’s hermeneutics within current debates on intercultural dialogue, new realisms and materialisms, and (post)critique.

Explore more of his work on his academic profile page and Google Scholar.

No comments:

Post a Comment