A post by Marta Roriz

Introduction

Tourism has today a significant impact on cities and urban lives around the world. Urban tourism and the exploration of local topographies as tourist destinations have led to a complex co-production and co-consumption of urban spaces by tourists and local residents. The significative increase of tourism following the Second World War, in both developed and developing countries, is the result of various economic, technological, social and political changes (Wearing, Stevenson and Young 2010; Graburn 1989; Urry 2002), leading Crick (1989: 310) to describe it as “the largest movement of human populations outside wartime”. People travel for pleasure, but also to experience new places as well as to return to the familiar and the known. Some are motivated to learn about other people and cultures, while others seek to gain insights into the self through travel (Wearing, Stevenson and Young 2010). If we define tourism to be “any kind of travel activity that includes the self-conscious experience of another place” (Chambers 2009: 6), then cities have much to offer, from museums to monuments, from memorials to restaurants, theatres and parks, there is much for the contemporary flâneur 1 to dwell. Cities, especially capitals, became the ideal locus for the provision and presentation of culture. But cities are not only open-air museums, repositories of art and heritage, but also places of work and home to large populations. The functional aspect of cities makes touring a complex undertaking that requires the tourist to make sense of the landscape, the built environment from which meaning can be derived (Metro-Rolland 2011). Academic contributions on tourism have become increasingly critical and sophisticated with the insights of social science disciplines, including anthropology, geography, sociology and interdisciplinary areas such as cultural studies. Morgan and Pritchard (1998) argued for a need to gain a deeper understanding of the tourism phenomenon by considering the actual experiences of tourists as they travel, the tourist reality, and to take into account the lived dimensions of tourism (1998: 12).

MacCannell (1989) suggested that the tourist was one of the best models available for the modern individual in general, arguing that the modern tourist recognises the inauthenticity of contemporary social life, relating its figure to that of a secular pilgrim in search of the authentic, and that through sightseeing, he is “striving for a transcendence of the modern totality, a way of attempting to overcome the discontinuity of modernity” (MacCannell 1989: 13). For Picard (2002) the tourist becomes a social fact, articulated by the social world of the locals and the social world of the tourists. The specificity of the relation of these two lies in their interactivity. The framing of the tourist as pilgrim seeking to challenge the discontinuity of modernity is fundamental to understand the emotive, reflexive, and affective component of heritage and landscape interpretation in Sarajevo. Its landscapes scarred by time, bearing traces of hope and desolation, are a “living” and open archeological site from which the tourist, as a contemporary flâneur engaged in the archaeological process of unearthing the myths and collective dreams of modernity (Frisby 1986), can read stratigraphy, the material evidences of time and transition, of former collective dreams and historical events with their war scars, signs of life and death, nostalgia and memory of things past.

The cityscape with its memorials and museums, its recent traces of war and atrocities, its urban cemeteries, of which some are improvised burial grounds that merge with everyday urban life, are an invitation to memory of global history events and emotions of nostalgia, with acts of remembrance about the “lost futures of modernity” (Fisher 2012). The construction of memory through manufactured heritage dispositifs that punctuate the city occurs not only locally, for the locals who have a close biographical relationship to the place, but also more globally, through tourist interpretations of the place and its landscape, and the consumption and commodification of that same heritage for international tourists. 2 This symbiotic relationship between the cityscape with the touristscape, of locals and tourists, is at work as the city is experienced through both immediate sensation and memory of the past. Connections to previous and collateral knowledge of historical events are brought into these new semiotic encounters and become aligned with the new experiences of touring the city. The embodied presence in these specific places makes us make sense of what we see and learn, reconfiguring our own biography with the biography of the place.

Sarajevo’s main tourist attractions, easily listed and ranked on platforms such as Tripadvisor, have a clear and close relationship to war and nostalgia. Places such as Tunel Spasa, the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Gallerija 11/07/95, the City Hall and the National Library Vijećnica – rebuilt after the complete destruction of the library and the invaluable loss of books and important national documents which came to be referred as bookocide – the War Childhood Museum, ARK D-0 Tito’s Nuclear Bunker on the outskirts of the city, its urban cemeteries and war related guided tours are the main examples of the cultural tourist sites, which easily fall under the scope of nostalgia, one of the main components of tourism (Graburn 1995) and heritage making (Berliner 2012) but also under the scope of what has been described as dark tourism (Lennon and Foley 2000; Stone and Sharpley 2008).

War is a major modern issue with deep social pervasiveness and long-term consequences. It is also an important cultural time marker, as populations divide their history in three phases: “before the war”, “during the war” and “after the war” (Smith 1998). And if there is a war, there is tourism. The wars of the 1990’s and the siege of Sarajevo with its urban battlefields were “live” on television worldwide. As Smith (1998) suggests, wars have historically been an important stimulus for tourism, especially today with charter mass tourism. War is not just a time and a place of an event; it is the unfolding of an intense human drama in which leisure and tourism now play an increasingly important role (Smith 1998).

Graburn (1995) identified nostalgia, authenticity and hyper-reality as the main components of contemporary tourist motivation. There is nothing more “authentic” than the effects of war and genocide; as for nostalgia, it should be found in all historically conscious societies. For authors like Boym (2001, 2007), Jameson (1991), Ugresic (2002) and Fisher (2012) nostalgia is a condition of postmodernity, a feature of global culture, an “incurable modern condition” (Boym 2001: xiv) and a symptom of our age. According to Boym (2007), nostalgia is not anti-modern, but coeval with it, resulting from a new understanding of time and space that enabled the division between “local” and “universal” (Boym 2007).

Nostalgia in Sarajevo is linked to cultural memory. With two world wars, disintegration of Yugoslavia and the post-socialist state after the 1990’s wars, it spilled over into politics and to rhetorical uses of the past. Boym (2007) begins her essay by pointing out that the 20th century began with a futuristic utopia and ended with nostalgia. While the optimistic belief in the future of the 20th century has become outdated, nostalgia never went out of fashion. In her view, nostalgia is not always retrospective but can be prospective, with a utopian dimension. It is just no longer directed towards the future. Sometimes it is not directed towards the past either, but rather sideways. The nostalgic feels stifled within the boundaries of time and space; it’s about the relationship between individual biography and the biography of groups or nations, between personal and collective memory (Boym 2007). Like progress, “nostalgia is dependent on the modern conception of unrepeatable and irreversible time” (Boym 2001: 13).

Thinking about the breakup of Yugoslavia and the bloody process of BiH’s (Bosnia and Herzegovina) independence, one is reminded of Ugresic’s phrase that if socialism relied on the promise of a utopia to come, capitalism feeds on a sense of loss to be filled with consumer goods (Ugresic 2002). Touristic attractions and the commodification and consumption of cultural memory fill our imaginaries and our need for identification in the post-1991 world, with the fall of communism and the announced (and now retracted) end of history (Fukuyama 1992). The end of history itself became a “hauntology”, a term rooted on Derrida (1994) that refers to the situation of temporal and ontological disjunction in which presence is replaced by a deferred non-origin represented by the figure of the ghost. Mark Fisher (2012) uses the term to describe contemporary culture, as haunted by the “lost futures” of modernity, which have been cancelled in postmodernity and with neoliberalism. Hauntology is described as “a pining for a future that never arrived” (Fisher 2012). Inspired by Berardi’s suggestion that we are culturally living “after the future”, Fisher (2012) argues that what haunts the 21st century is not so much the past as the lost futures that the 20th century taught us to anticipate. This meant accepting a situation in which culture would continue without change, Fukuyama’s end of history. Also inspired by Jameson’s (1991) nostalgia mode, Fisher (2012) argues that postmodernism is characterised by a particular kind of anachronism, linked to the idea that we are increasingly incapable to create representations of our own current experience. It may well be why this zeitgeist as described by Fisher (2012) resonates with Graburn’s (1995) conclusion that nostalgia is one of the key forces giving power to tourist attractions. The sentimental longing for feelings and things of the past can indeed explain how recreations of the past seem to have success on tourist attractions and experiences for sale. It is not unusual to find independent agents promoting retromania touristic experiences, dinners in typical socialist Yugoslav homes, furnished like in old socialist times, hostels decorated as war bunkers, and the selling of souvenirs relating to Tito, Jovanka and many socialist era symbols, 1990’s war fragments like real bullets turned into keychains. When talking about the creation of heritage and the production and consumption of tourist cultural experiences, Graburn says it responds to “one of the most powerful of all modern tropes of attraction: nostalgia” (1995: 166) even if it manifests itself in forms of dark tourism.

1 The original flâneur was regarded as a new kind of urban dweller who had the time to wander, watch and browse in the public spaces of the emergent modern city (Benjamin 1973). Benjamin adopted his concept from the poetry of Baudelaire’s archetype of the modern urban experience in the figure of the flaneur, the “botanist of the sidewalk”; the flâneur had a double role of participating in the city while remaining a detached observer. The flâneur was a poet and a stroller (see Harvey 2003); in a collection of texts organized by Tester (1994) the flâneur is described as an amateur detective (see Morwaski and Shields chapters in Tester 1994) observing the urban spectacle, people, and life while engaged in an archaeological process of unearthing the myths and collective dreams of modernity (Frisby 1986). He stood outside the production process, away from home in the search of the unfamiliar (Lechte 1995); characteristics that seem to fit the contemporary tourist (Urry 2002). For more on the relation of the flâneur with the tourist see Wearing, Stevenson and Young (2010).

2 The connection between tourism, nostalgia and gentrification of cities has been described in the literature, as having a role in place-marketing strategies, but also as producing erasures of the past (see for instance Bond and Browder 2019; Skoll and Korstanje 2014; Berliner 2012).

Tourism and ethnographic research: the ethnographic tourist, autoethnography and the use of photography in research

The study of tourism and touristification is now a productive and growing field that brings together different disciplines. Social anthropology is no exception. Its contribution, as well as of ethnographic methods is widely acknowledged (Chambers 2009; Graburn 2002; Nash 1981; Nash and Smith 1991; Sandiford and Ap 1998; Smith 1989). Tourism revolves around culture, which has long been the object and domain of anthropologists. Although some scholarship has been built around tourism, ethnographies of tourism have mostly been by-products of ethnographic research on other more traditional phenomena (Graburn 2002). This may be due to some kind of prejudice against the figure of the tourist. In his 1989 text, Bruner discusses the relationships and similarities between ethnographic tourism and colonialism, how they were in fact born together. Because of the similarities between the traveller-tourist and the ethnographer, for many anthropologists tourism was a blank spot, uncharted territory: “from the perspective of ethnography, tourism is an illegitimate child, a disgraceful simplification and an impostor (de Certeau 1984: 143 in Bruner 1989) and we strive to distinguish ethnography from tourism, for tourism is an assault on our authority and privileged positions as ethnographers” (Bruner 1989: 439). In fact, it has been argued that the tourist and the anthropologist have a close relation, since they both share common origins which can be traced to the explorer, the missionary, the merchant and the traveler (Galani-Moutafi 2000). Along with adventurers and wanderers, early travelers have been characterized as proto-anthropologists and proto-tourists (Crick 1985: 76), so this relation of the anthropologist and the tourist rests on the early origins of anthropology itself, of travel and the encounter between the self and other.

Concerning urban ethnography and the focus on cities, there is a long tradition in anthropology, and also close relationship with travel writing. In their introduction to urban ethnography, Duneier, Kasinitz and Murphy (2014) explain that at the core of the urban ethnographic enterprise is the idea that observing people in their everyday contexts in various unstructured situations over a period of time can provide clues as to how they construct and make sense of their world (Duneier, Kasinitz and Murphy 2014: 2). But beyond the importance of the personal experiences of those being observed, there’s also the experience of the observer. The latter has, in fact, become the means by which ethnography is produced. The declared inclusion of the ethnographer’s experience has been the subject of an immense body of work in anthropology. Reflexivity about the condition and position of the ethnographer has become an important part of the ethnographic enterprise. This reflexive turn, as labelled in debates of 1980’s, was a product of the anthropologists’ awareness of the limitations of their traditional research frameworks. The whole ethnographic project had been challenged on both ethical and scientific grounds (Clifford and Marcus 1986; Marcus and Fischer 1986), a moment referred to as the crisis of representation. Fieldwork wasn’t what it used to be. Instead of whole people and whole communities, anthropologists recognized that, from then on, they would have to write more composite descriptions of fragments of people. Objects and subjects were on the move, the world was changing. Movements of people, capital, technology, cultural and political values, the then new cultural dimensions of globalisation (Appadurai 1996) changed not only perceptions but also methods. The mobility turn emerged in contrast to the more static traditional ways of the social sciences, which rarely captured movement and trivialised “the importance of the systematic movements of people for work and family life, for leisure and pleasure, and for politics and protest” (Sheller and Urry 2006: 208). The mobilities paradigm allowed us to see movement and fluxes as part of our condition, including tourism and travel. With postmodern developments in anthropology, methodology followed. Ethnographic practices became global (Burawoy et al. 2000) and multi-sited (Marcus 1995). These new approaches reformed the discipline in order to encompass the accelerated pace of the globalised world in all its complexity. Ethnography on a global scale would examine the forces, mechanisms and social effects of globalization with its compression of time and space; it would see the world as existing in networks, scapes and flows. Not surprisingly, the expansion of tourism in recent decades becoming a major social, cultural and economic phenomenon has attracted the eyes of the ethnographer, as well as the assumption of a distinction between the tourist and the traveller as qualitatively different is one that continues to prevail in both academic literature and popular imagination (Wearing, Stevenson and Young 2010). 3

In his chapter “The etnographic tourist”, Graburn (2002) develops on the contemporary practice of ethnography with mobile objects and discusses the strategies for undertaking such research, focusing on the figure of ethnographer which becomes himself a tourist. He talks about how if you aim to ethnographically observe tourists, you have to become one. The tourist becomes a “native”. A kind of autoethnography using one’s own subjective experience, being both object and observer, “being there” as form of participant observation. The present essay departed precisely from my own position as an ethnographic tourist, being an ethnographer and a previous traveller in several post-Yugoslav countries, I decided to focus a stay in Sarajevo for a month with the aim of exploring and ethnograph its local tourist attractions experiences.

Tourism through the lens of experience is not a new approach, and a number of authors have built on autoethnography in travel and tourism research (Beeton 2022; Buckley and Cooper 2022) as well as argued for nuanced approaches to the study of tourism which engages with the subjective and experiential (Desforges 2000; Harrison 2003; Cary 2004; Noy 2004; White and White 2004; Wearing and Wearing 2001; Wearing, Stevenson and Young 2010). As Wearing and Wearing state:

“The theorization of tourism […] needs […] not only to recognize the interrelation of the site and the activities provided […] at the tourist destination, but requires a fundamental focus on the subjective experience itself. While not being divorced from its sociological contextualization, the involving experience allows for the elaboration upon the role of the individual tourists themselves in the active construction of the tourist experience.” (2001: 151)

The idea of the tourist as something of a flâneur – the urban dweller who had the time to wander, watch and browse in the public spaces of the emergent modern city (Benjamin 1973) – resonates with the modern traveller who can acquire experiences and undergo transformations having the journey as a type of passage in time. The interlocking dimensions of time and space make the journey a potent metaphor that symbolizes the simultaneous discovery of self and the other. It is precisely this capacity for mirroring the inner and the outer dimensions that makes possible the inward voyage, whereby a movement through geographical space is transformed into an analogue for the process of introspection (Galani-Moutafi 2000: 205). According to Urry (2002), the 19th century literary construction of the flâneur can be regarded as a forerunner of the 20th century tourist in that both were generally seen to be escaping the everyday world for an ephemeral, fugitive and contingent leisure experience (Stevenson 2003 in Wearing, Stevenson and Young 2010).

For this ethnographic essay, to be an ethnographic tourist entailed analytical autoethnography, which in tourism research involves direct and detailed observation of a researcher’s own perceptions, emotions, thoughts, and actions while approaches include retrospective, experimental, and collaborative (Buckley and Cooper 2022). Data sources used for the present work included being there up close, taking notes, informal conversations, photography records, multimedia and media research, social media, but also my personal memories and historical recollections of local and global events since the 1990’s in this region. As Buckley and Cooper (2022) elaborate, in tourism research, analytical autoethnographies can address these experiences, as well as tourists, attractions, and activities; and autoethnographic methods are a specialised tool, most valuable where a researcher’s experience provides data or insights at greater depth or detail than available otherwise. Also, for the present work photography was of particular importance, not only as a visual anthropology method (Collier and Collier 1986), an aide mémoire technique, but also for picturing experience (Sather-Wagstaff 2008).

Works on the history of photography and travel (Osborne 2000; Hirsch 1997; Larsen 2005) have documented how photographs become historically-specific modes of knowledge production, speaking to why we take and use photographs (Sather-Wagstaff 2008). According to Sather-Wagstaff: “photographs are devices for the performance of subjectivities, for the making of various social relationships and cultural realities, and most importantly, for memory, recalling the past in service to the present” (2008: 81). Through touristic photos and visual media as a form of practice, more than representation, we take part in the world, continually making individual and collective worlds meaningfulness (Sather-Wagstaff 2008). As Osborne elaborates:

“Like arrangements of stones, monuments, flags, markings on walls or trees, travel is one of the means of leaving our presence in and on the indifferent surfaces of the world. Travel is often guided by such markers and frequently includes the making of them. Photography, too, marks our presence in a place, or rather, has the place mark its presence in our images.” (2000: 187)

The photographic record built through my travel provided an archive to be utilised as content and illustration in this research. I utilised my position as ethnographer, as tourist and as snapshooter 4 for engaging in informal and formal conversations with locals, tourists, and tourism agents such as hosts, tour guides, and museums personnel.

The practice of ethnography and autoethnography towards the global has brought us across connections, namely the locating of the site in relation to place-making projects (Gille and Ó Riain 2002). The extension of the site in time and space posed practical and conceptual problems for ethnographers (Gille and Ó Riain 2002), and they developed the notion of place-making projects following Appadurai’s (1996) production of locality. Place making projects “seek to redefine the connections, scales, borders, and character of particular places and particular social orders. These projects are the critical sites through which global ethnographers can interrogate social relations in an era of globalisation” (Gille and Ó Riain 2002: 277).

Tourist attractions in Sarajevo, the most visited places, can be analyzed as place making projects, as produced locality. But there are other frameworks for ethnographic research if we take the case of tourism research. Instead of global ethnography, Salazar (2005) calls for “glocal ethnography”, building on Robertson’s (1995) notion of glocalization, a term developed to better grasp the many interconnections between the global and the local and their two-way dialectic. He defines glocal ethnography as a fieldwork methodology for describing and interpreting the complex connections, disconnections and reconnections between local and global phenomena and processes. In contrast to Burawoy’s approach to global ethnography (in Burawoy et al. 2000), the emphasis is not on the global but on the complex ways in which the local and the global are linked, just like the events unfolded in BiH brought them to the present post-socialist order.

Following the framing of glocal ethnography, the next section offers a description of the touristed landscapes (Cartier and Lew 2005) of Sarajevo and some of its main tourist sites, aiming to highlight how both social worlds of the locals and tourists collide, but also how these sites function as produced locality, where global and major political events spilled over and are entangled to local history.

3 Ethnographers working on this distinction are interested among other concerns, on questions about the cultures of meaning, mobilities and engagement that frame and define the tourist experience and the traveler identity; which subjective realities and experiences (imagined or otherwise) can distinguish the traveller and the tourist; what it is that “they” are looking for when they travel, be embarking on a package tour, or immersing themselves in the places, cultures and lifestyles of the ecological or exotic “Other” (Wearing, Stevenson and Young 2010).

4 I don’t feel comfortable portraying myself as a photographer, hence the snapshooter since I am using photographs and snapshots as means, as documents, archive, instant-reality images and aide mémoire.

Sarajevo, the place that ended the 20th century

“Sarajevo, the place that ended the 20th century”, a phrase we can read on the wall of one of the most popular tourist sites among tourists in Sarajevo, the Tunel Spasa, the Tunnel of Hope. Most guided tours in Sarajevo, as well as Tripadvisor and other online platforms for travellers present the tunnel as the most important tourist attraction in the city. It’s not surprising, as the tunnel was a major achievement during the war, allowing Bosnian-held territory to be connected and contributing significantly to the survival and resistance of Sarajevo citizens during the 44-month siege in the 1990’s.

Figure 1 – Tunel Spasa

Source: photo by the author.

Curiously, this inscription on the wall corresponds with Eriksen’s (2015) observation that the world as we know today, the beginning of 21st century, began precisely in 1991. It was the year of the breakup of Yugoslavia, followed by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It marked the end of the Cold War and the two-bloc system that had defined the post-II World War period, with its ideological conflict between socialism and capitalism. In 1991, Yugoslavia began to disintegrate with surprising violence, fueled by a kind of nationalistic sentiment that many thought had been overcome during the Tito years. Identity politics wasn’t a thing of the past as the rise of nationalisms in the Eastern bloc could attest (Eriksen 2015: 17). The year 1991 was also when the Internet began to be marketed to ordinary consumers, and the new pocket-sized mobile phones began to spread across the world. The deregulation of markets that had taken place in the previous decade with the rise of neoliberalism, the effects of a weaker state and a less manageable and predictable market, were now being felt, aided by new information and communication technologies. This post-1991 world is seen by Eriksen (2015) as one of heightened tensions and frictions of hotter, faster and denser networks of interconnectedness, with repercussions everywhere, constituting an overheated world due to the accelerated pace of the economic globalisation. The proper notion of global warming feeds into this larger and enduring story about “acceleration, which, in a sense, is the story of modernity as such” (Eriksen 2015: 16).

This was the time Fukuyama branded as the end of history. With humanity reaching not only the end of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history itself, with the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government (Fukuyama 1992).

The Balkans, and Bosnia in particular, have historically been at the cross-roads of many empires. Sarajevo became not only the place which marked the end of the 20th century, but was also the place that marked its beginning, with the start of First World War with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Gavrillo Princip near Sarajevo’s Latin Bridge.

Looking at Sarajevo’s urban landscape, its cityscape, it’s easy to see how different eras, empires and wars punctuated and organised its topography as if an almost perfect temporal timeline has been physically drawn. From the 15th century Baščaršija, the cultural center of the old town, legacy of the Ottoman empire, you walk straight into Austro-Hungarian part of the city, through the buildings of Ferhadija, a pedestrian street, to the Eternal Flame monument to the victims of the World War II, just before Tito Street, so symbolic and allusive to the Yugoslav socialist period. Then to the famous Sniper Alley, the informal name for the streets Zmadja od Bosne Street and Meša Selimović Boulevard, the main boulevard during the 1990’s Bosnian war. This zone was lined with sniper posts and became famous for the danger it posed to civilians passing through. Images of it were popularised in media and news at the time but also through replicas and simulations for American films like Welcome to Sarajevo, The Peacemaker or In the Land of Blood and Honey. The urban guerrilla atmosphere globally presented in real-life TV news reports during the war years entered popular culture. Alfonso Cuarón, the director of Children of Men, reported on how he was inspired by these images of the urban Yugoslav wars to meticulously construct his film pervading atmosphere.

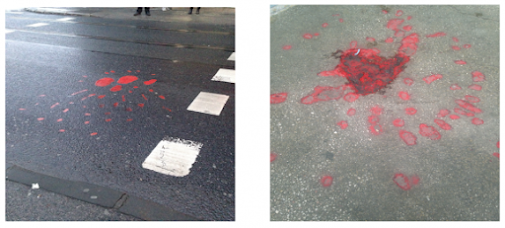

This physical and temporal line ends precisely in the tunnel, which today forms a monumental complex recognised by the Law on the Protection of Cultural Heritage since 2010. It’s a line that begins in the historical and cultural center of the old town and ends in the industrial area of the city, and on to the airport where the tunnel had its end line. This linear organisation of the city is also interrupted by the old cemeteries and sometimes improvised burial grounds, now turned memorial cemeteries, that have changed the cityscape inscribing in the minds of ordinary passengers constant reminders of death and atrocity, as well as the numerous memorials to the war, such as the Sarajevo Roses, red ink patches on the ground, that mark spots where mortar shell explosions caused deaths.

Figure 2 – Sarajevo Roses on the streets

Source: photos by author.

Not only different periods and historical events become visible, materialised in the architecture and landscape of the city, but also the social and ethnic/religious backgrounds and divisions that have reconfigured the city in post-Dayton BiH. The urban cemeteries which merge with the city’s streets are visibly marked by ethnicity and religious background just by looking at the shapes of the gravestones. 5 The 1984 Olympic venues and the Koševo Olympic Stadium, which became a cemetery for the victims of the siege, are particularly striking.

Figure 3 – A composition of photos by the author of Kosevo Olympic Stadium and surrounding venues where the Kosevo Martyrs’ Cemetery and war memorial now are overlapped

The Olympic venues of Sarajevo today function as a double reminder: on the one hand, of the celebration of nations through sport, Yugoslavia was the first communist country to host the Winter Olympics, so this was an important historical event; and, on the other hand, parts of these Olympic venues used for Bosnian Serb offensives, also became a reminder of the violence and prolonged siege.

Figure 4 – Composition of photos by the author during one of the war tours in abandoned 1984 Olympic Games venues. The bobsleigh and luge track as well as other buildings had been appropriated during war, namely functioning as artillery posts during the siege

Most of these Olympic venues are abandoned, full of bullet holes and cracks. The bobsleigh and luge track at the top of the city were used by Bosnian Serb artillery stronghold, and the city ski jump was used as artillery position. These sites are shown on the many offers of guided tours about the war, where graffiti spotting coincides with faded images of Vucko, the Olympic mascot. Some of the most important buildings have been restored, such as Skenderija Hall, which now attracts many visitors. The people of Sarajevo are proud of the 1984 Olympic Games and celebrate its anniversary every year at Koševo Stadium.

The mythology of the state, and of the city itself, has branded Sarajevo as the Jerusalem of Europe, a place where cultures meet, as it is written on the floor of Ferhadija Street, where East meets West. On the one hand, this culturally diverse history and heritage are celebrated and disseminated in official discourses and tourist brochures, proudly presenting Sarajevo as a city with a mosque, catholic church, an orthodox church and a synagogue within the same neighborhood, while on the other hand the traces of violence and the bloody disintegration of Yugoslavia are still very visible. The dissolution of Yugoslavia 6 was bloody and contentious, leading to war and the mass destruction of cities such as Vukovar, Mostar and Sarajevo, which endured the longest siege of modern times, 7 and the revival of concentration camps back in Europe since World War II, as well as the trauma of genocide with the events in Srebrenica in 1995. The death toll in BiH alone is estimated at over 200.000, with three million refugees and war-affected people. 8

Figure 5 – A commemorative billboard of the 20th year of the genocide amidst other adverstising billboards.

Source: photo by the author

The current political situation in Sarajevo and BiH has been described by Mujkic (2007) as an ethnopolis, with a tripartite government based on the logic of the Dayton Peace Accord cemented in the constitution designed by a foreign-enforced consociation of three nationally defined constituent peoples: Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs. This constitutional framework has been described by Mujkic (2007) as promoting a procedural democracy only among the political representatives, or as he describes the ruling oligarchies, of the three ethnic groups. A new type of ethnic democracy that challenges the values of the individual as an abstract citizen, by restricting individuals to identifying and representing themselves solely on ethnic affiliation. A citizen of BiH is recognised only as a member of an ethnic group, and only through this recognition is he/she recognised as a member of political community (Mujkic 2007). This has been a source of many problems, overshadowing other forms of individual citizenship, people who don’t fit into the category of constituent peoples, with hybrid identities, such as the Yugoslavs, Roma, and others. Indeed, as Mujkic (2007) points out, there is little to their ethnicity other than their religiosity. Religion is politically instrumentalised because religious activities serve as a means of ethnic mobilisation and homogenisation. The notion of “constituent peoples” is highly obscure, but key to Bosnian ethnopolitics, with these three identities structurally privileged through the electoral system and in public life where quota systems are used. This ethnopolitics locks people within ethno-religious categorisation leaving no room for freedom of self-identity. In his ethnography in a Sarajevo apartment complex, Jansen (2015) described the lives in post-Dayton BiH as being prevented from living a “normal life”, as lives lived in the “meantime”. He explores this term as a symptom of spatio-temporal entrapment of life in BiH, an exposure to surveillance by an outside gaze in a semi-protectorate where everything is experienced as being in a limbo.

Its citizens live in mutual recognition of difference, negotiating individual identities in the midst of history, collapse and nation-building, political stagnation and a built environment scarred by war and atrocities. Yugoslav legacies face a paradox of invisibility and visibility, of presence and disappearance. Within the framework of compulsory ethnic identity imposed since the end of the war, people refer to nostalgic feelings about what was lost in the transition from the socialist past, about what was lost in the war. Yugoslavia was once the leader of the Non-Aligned Movement. With its demise, it is now divided into several peripheral countries facing long processes of transition to market economies as well as a distant possibility of EU integration. This may well be one of the reasons for expression of yugonostalgia, for people’s nostalgia for the past. According to Volčić, the brutality of the destruction and ethnic killings that occurred in the former Yugoslavia in the wake of the collapse of socialism plays a significant, if not critical, role in framing and filling post-war yugonostalgia and its representations (Volčić 2007: 27).

5 Due to different styles of tombstones in Catholic, Orthodox and Muslim traditions.

6 The breakup of Yugoslavia and the start of the conflicts is beyond the scope of this essay but see Misha Glenny (1996) “Fall of Yugoslavia”, and “Yugoslavia death of a nation” by Silber and Little (1997) for a detailed analysis.

7 For a detailed view on Sarajevo under siege see the ethnography by Macek (2009).

8 See Bougarel, Helms and Duijzings (2007), Bassiouni (1994), Gow (2003).

Touristic attractions in Sarajevo: dark tourism and reflective nostalgia

A quick search on platforms such as Tripadvisor or Lonely Planet shows how Sarajevo’s top tourist attractions are linked to the Bosnian war of the 1990’s. Among the recommended “things to do” are the popular war guided tours and life during the siege tours. These tours, offered by local guides who lived through the city’s hardest times, provide first-hand information, stories and lived experience of the city during the war, showing international tourists the main sights of battlefields, frontlines, houses of wartime leaders and other similar attractions, between street memorials and monuments, usually ending in the Tunnel of Hope. This type of activity falls under thanatotourism, or the growing specific field of dark tourism (Lennon and Foley 2000; Stone and Sharpley 2008), an umbrella term related to the representation and consumption of real sites of death and disaster, sites associated with war, death and atrocity. Dark tourism includes other more specific forms and practices of tourism, such as war-related associated with war museums and memorials, genocide tourism, grief and mourning tourism, among others. There has been growing academic attention to these darker sides of travel, framing dark tourism practices in relation to a perceived “intimation of postmodernity” (Lennon and Foley 2000: 11), claiming that dark tourism sites challenge the inherent order, rationality and progress of modernity, as does the concept of postmodernity, and that at most of these sites, the boundaries between the message (educational, political) and their commodification as tourist products have become increasingly blurred (Lennon and Foley 2000). Dark tourism is becoming a cultural expression that opposes the suppression of death from collective life in global consumer culture with its ideology focused on life and youth. In this intimate consumption of the death of others, the contemporary tourist can be associated with contemplations of his own mortality and experience. These appeals to the discontinuous impulses of the contemporary age are expressed in Giddens (1991) pervasiveness of reflexivity, the systematic and critical examination, monitoring and revision of all beliefs, values and practices in the light of changing circumstances. This ongoing process of systematic and potentially radical reassessment of contemporary life can condemn the individual to a pervasive “radical doubt” (Giddens 1991: 21) and a perceived reduction of the ontological security. In this sense, dark tourism destinations may well be the search for more meaningful destinations and purposes.

In addition to the places explored in war tours, visitors seem to include in their itineraries the War Childhood Museum, Gallerija 11/07/95, the National History Museum of BiH, the Museum of Crimes against Humanity and Genocide and ARK D-0 Tito’s Nuclear Bunker, the latter very popular for Cold War enthusiasts. These are all places of collective memory. Most importantly, these places tell the story of Sarajevo, Bosnia and the region throughout the 20th century, from the beginnings of Yugoslavia, through Socialist Yugoslavia and its fall with the end of the two bloc-system marked by war.

These spaces, museums, memorials and monuments seek to remember the past in order to not forget what happened, and to prevent its recurrence in the future. The creators of these sites offer a reading of past events based on a particular arrangement of objects, lighting and spaces with the goal of offering the visitor a particular version of what they intend to present. As a result, the sites serve to denounce and memorialize conflicts, victims and perpetrators.

In the case of Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, it has a thematic structure and museological presentation of history from the arrival of the Slavs on the Balkan Peninsula to the present day. The museum was divided in two permanent thematic exhibitions “Bosnia and Herzegovina through the centuries” and “Surrounded Sarajevo” in remembrance of life during the siege. Special attention was paid in its presentation to the period of BiH before and after the war, with the museum assuming these periods as important areas of research. In the display of the period between 1945 and 1990 we see recreations of the typical Yugoslav apartments decorated with Yugoslav appliances, mid-century Yugoslav furniture, kitchen appliances, radios and other objects of consumer culture, memorabilia such as advertisements for products, cars, and other elements of everyday life in former Yugoslavia. In the exhibition of post-1990 period the museum recreates historical episodes of the war with real memorabilia and material objects, such as a Markale market stall to illustrate the bloody attack on the Markale market, newspapers, photographs, cigarettes which became an important currency during the war, military equipment, weapons, clothing, Unprofor 9 material and canned food, the Bosnian militia clothing – ordinary jeans and sneakers – and other important items are organised in the collection along a timeline of facts.

Figure 6 – exhibitions of the History Museum of BiH

Source: photos by the author

The War Childhood Museum 10 and its collection, which started as a private initiative, gathered a set of toys, diaries, personal belongings, photographs, items of clothing among other objects donated by war survivors to give personal insights into stories about what was like growing up during the war. The display of victims’ personal possessions can add to the authenticity or poignancy of the visitor experience, giving additional meaning to often mundane objects. Their use aims to elicit an emotional response from the viewer. This can also be achieved through photographs, such as those exhibited in Gallerija 11/07/95, a memorial gallery that aims to preserve the memory of Srebrenica through a range of multimedia content, namely portraits of victims’ faces and photographs of mass graves and collective funerals. The memory and experience of genocide is still a very powerful element of contemporary life, with evidence and mass graves still appearing, and an ongoing process of identifying the dead till this day.

When tourists interact with these sites, they assume an active role in relation to the objects and spaces associated with these events. Apart from the fact that they did not experience them first-hand like the locals, they become close and familiar with these experiences through the particular configurations and displays of the site. The materials and objects on display encapsulate the past of a particular community. They serve as portable places that transport individuals to different places and times (Kidron 2012).

Remembering the past, either through Boym’s (2001) reflective nostalgia for the unrealised dreams of the past or through Fisher’s (2012) notion of hauntology and lost futures, is also remembering what could have been, through the recognition of unrealised paths, so that these recognitions affect the present. In the particular case of yugonostalgia, Ugresic (2002) describes it as a productive revisiting of the collective experiences of citizens whose individual lives were embedded in the social life of the collapsed state. Yugonostalgia becomes a vital, productive tool in the emotional reconstitution and preservation of history. The phenomenon can also be understood, as Bošković (2013) suggests, as an implicit critique to the current socio-political realities in which former Yugoslavs live. Yugonostalgia is an affirmation that history could have been different, that the paths taken were not the only possible ones; in this view, nostalgia represents a potential engine and means of emancipation. Underlying nostalgia is the desire for a better world (Bošković 2013).

9 The United Nations peacekeeping mission at the time in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/unprofor.

10 See https://warchildhood.org.

Concluding remarks

The aim of this essay was to provide a description of the touristed landscape and tourist attractions of Sarajevo, from the position of the ethnographic tourist and the exercise of ethnographic flânerie in Sarajevo. From descriptions of the built environment to the top tourist attractions, the individual biography of the global citizen-tourist aligns with biographies of place. Glocality is exercised. The essay also attempted to contribute to current knowledge about the motivations of contemporary tourists in search for meaningful experiences, which become salient in the many forms of tourism, especially dark tourism, in this particular region of the Balkans where our post-1991 global world order has left a significant and indelible mark. Using the concepts of hauntology and nostalgia as starting and guiding ideas, the experience of touring the city, the aim was to allude on how the social worlds of locals and tourists collide, and how the global and the local are merged, in an autoethnographic account. Through the landscape, heritage, and the war wounded sites that compose the tourist trajectories of Sarajevo it was possible to offer a portrayal of the political realities as well as images of the past. In the case of Sarajevo one can see the impact of global historical developments with their brutal consequences at the local levels. Former ideas of socialism and modernism, with their promise of utopia, also died in Sarajevo to become hauntologies, to be consumed as tourist products, as ruminations. The nostalgia in Boym’s reflective suggestion might allow us to look back on our modern history in prospective terms, or at least from there we can look at unrealised possibilities and collective dreams beyond the haunted old futures that turned out obsolete.

The Bosnian case brought here is also interestingly becoming a preview of the current scenario in Europe, with the war in Ukraine. When the Ukrainian war ends, if it ends and how it will end, is a future which will also become a past. A past to be negotiated, disputed, written, monumentalised and memorialised, to be later on consumed, for sale, visited and toured.

Etnográfica was where this article was first released.

Bibliography

APPADURAI, Arjun, 1996, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

BASSIOUNI, Cherif M., 1994, Final Report of the UN Commission of Experts Established Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 780 (1992) – Document S/1994/674. New York: United Nations. Available at https://www.icty.org/x/file/About/OTP/un_commission_of_experts_report1994_en.pdf (last consulted January 2025).

BEETON, Sue, 2022, “Autoethnography in travel and tourism”, Unravelling Travelling: Uncovering Tourist Emotions through Autoethnography (The Tourist Experience). Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, 45-63.

BENJAMIN, Walter, 1973, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism. London: New Left Books.

BERLINER, David, 2012, “Multiple nostalgias: the fabric of heritage in Luang Prabang (Lao PDR)”, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 18 (4): 769-786. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/23321449 (last consulted January 2025).

BOND, Patrick, and Laura BROWDER, 2019, “Deracialized nostalgia, reracialized community, and truncated gentrification: capital and cultural flows in Richmond, Virginia and Durban, South Africa”, Journal of Cultural Geography, 36 (2): 211-245. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2019.1595914.

DOI : 10.1080/08873631.2019.1595914

BOŠKOVIĆ, Aleksandar, 2013, “Yugonostalgia and Yugoslav cultural memory: lexicon of yu mythology”, Slavic Review, 72 (1): 54-78. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.5612/slavicreview.72.1.0054.pdf (last consulted January 2025).

BOUGAREL, Xavier, Elissa HELMS, and Ger DUIJZINGS, 2007, The New Bosnian Mosaic: Identities, Memories and Moral Claims in a Post-War Society. Surrey: Ashgate.

BOYM, Svetlana, 2001, The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books.

BOYM, Svetlana, 2007, “Nostalgia and its discontents”, The Hedgehog Review, Summer 2007: 7-18. Available at https://hedgehogreview.com/issues/the-uses-of-the-past/articles/nostalgia-and-its-discontents (last consulted January 2025).

BRUNER, Edward M., 1989, “Of cannibals, tourists and ethnographers”, Cultural Anthropology, 4 (4): 438-445.

DOI : 10.1525/can.1989.4.4.02a00070

BUCKLEY, Ralf, and Mary-Ann COOPER, 2022, “Analytical autoethnography in tourism research: when, why, how, and how reliable?”, Tourism Recreation Research, 49 (6): 1238-1246. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2155784.

DOI : 10.1080/02508281.2022.2155784

BURAWOY, Michael, et al., 2000, Global Etnography: Forces, Connections, and Imaginations in a Postmodern World. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

CARTIER, Carolyn, and Alan A. LEW, 2005, Seductions of Place: Geographical Perspectives on Globalization and Touristed Landscapes. London, New York: Routledge.

CARY, Stephanie Hom, 2004, “The tourist moment”, Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (1): 61-77. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.03.001.

DOI : 10.1016/j.annals.2003.03.001

CHAMBERS, Erve, 2009, Native Tours: The Anthropology of Travel and Tourism. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press Inc.

CLIFFORD, James, 1988, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press.

DOI : 10.4159/9780674503724

CLIFFORD, James, and George E. MARCUS, 1986, Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

DOI : 10.1525/9780520946286

COLLIER, John, and Malcolm COLLIER, 1986, Visual Anthropology: Photography as a Research Method. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

CRICK, Malcolm, 1985, “ ‘Tracing’ the anthropological self: quizzical reflections on field work, tourism, and the ludic”, Social Analysis – The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice, 17: 71-92. Available at https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/ielapa.860201613 (last consulted January 2025).

CRICK, Malcolm, 1989, “Representations of international tourism in the social sciences: sun, sex, sights, savings, and servility”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 18: 307-344. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2155895 (last consulted January 2025).

DOI : 10.1146/annurev.an.18.100189.001515

DERRIDA, Jacques, 1994, Specters of Marx, the State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, & the New International. New York: Routledge.

DESFORGES, Luke, 2000, “Travelling the world: Identity and travel biography”, Annals of Tourism Research, 27 (4): 926-945. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00125-5.

DOI : 10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00125-5

DUNEIER, Mitchel, Philipe KASINITZ, and Alexandra K. MURPHY, 2014, The Urban Ethnography Reader. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

ERIKSEN, Thomas H., 2015, “Divided by a shared destiny: an anthropologist’s notes from an overheated world”, in Thomas H. Eriksen et al. (eds.), Anthropology Now and Next: Essays in Honor of Ulf Hannerz. New York: Berghahn Books, 11-28.

FISHER, Mark, 2012, “What is hauntology?”, Film Quarterly, 66 (1): 16-24. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16 (last consulted January 2025).

DOI : 10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16

FRISBY, David, 1986, Fragments of Modernity: Theories of Modernity in the Work of Simmel, Kracauer and Benjamin. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

FUKUYAMA, Francis, 1992, The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Avon Books.

GALANI-MOUTAFI, Vasiliki, 2000, “The self and the other: traveler, ethnographer, tourist”, Annals of Tourism Research, 27 (1): 203-224.

GIDDENS, Anthony, 1991, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in Late Modern Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

GILLE, Zsuzsa, and Séan Ó RIAIN, 2002, “Global ethnography”, Annual Review of Sociology, 28: 271-295. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.140945.

DOI : 10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.140945

GLENNY, Misha, 1996, The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War. London: Penguin Books.

GOW, James, 2003, The Serbian Project and Its Adversaries: A Strategy of War Crimes. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

DOI : 10.1515/9780773570306

GRABURN, Nelson H., 1989, “Tourism: the sacred journey”, in Valene L. Smith (ed.), Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 21-36.

GRABURN, Nelson, H., 1995, “Tourism, modernity and nostalgia”, in Akbar A. Ahmed, and Cris Shore (eds.), The Future of Anthropology: Its Relevance to the Contemporary World. London: Athlone Press, 158-178.

GRABURN, Nelson H., 2002, “The ethnographic tourist”, in Graham Dann (ed.), The Tourist as a Metaphor to the Social World. New York: Cabi Publishing, 19-40.

HARRISON, Julia, 2003, Being a Tourist: Finding Meaning in Pleasure Travel. Vancouver: UBC Press.

DOI : 10.59962/9780774850391

HARVEY, David, 2003, Paris: Capital of Modernity. New York: Routledge.

HIRSCH, Marianne, 1997, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

JAMESON, Frederic, 1991, Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

DOI : 10.2307/j.ctv12100qm

JANSEN, Stef, 2015, Yearnings in the Meantime ‘Normal Lives’ and the State in a Sarajevo Apartment Complex. New York: Berghan Books.

DOI : 10.3167/9781782386506

KIDRON, Carol A., 2012, “Breaching the wall of traumatic silence: holocaust survivor and descendant person-object relations and the material transmission of the genocidal past”, Journal of Material Culture, 17 (1): 3-21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183511432989.

DOI : 10.1177/1359183511432989

LARSEN, Jonas, 2005, “Families seen sightseeing: performativity of tourist photography”, Space and Culture, 8 (4): 416-434. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331205279354.

DOI : 10.1177/1206331205279354

LECHTE, John, 1995, “(Not) Belonging in postmodern space”, in Sophie Watson and Katherine Gibson (eds.), Postmodern Cities and Spaces. Oxford: Blackwell, 97-111.

LENNON, John, and Malcolm FOLEY, 2000, Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster. London: Continuum.

DOI : 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.212

MACCANNELL, Dean, 1989, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Schocken Books.

DOI : 10.1525/9780520354050

MACEK, Ivana, 2009, Sarajevo Under Siege: Anthropology in Wartime. Philadelphia, PN: University of Pennsylvania Press.

DOI : 10.9783/9780812294385

MARCUS, George E., 1995, “Ethnography in/of the world system: the emergence of multi-sited ethnography”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 24: 95-117. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2155931 (last consulted January 2025).

DOI : 10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523

MARCUS, George E., and Michael J. FISCHER, 1986, Anthropology as Cultural Critique. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226229539.001.0001

METRO-ROLLAND, Michelle, 2011, Tourists, Signs and the City: The Semiotics of Culture in Urban Landscape. Surrey: Ashgate.

MORGAN, Nigel, and Annette PRITCHARD, 1998, Tourism Promotion and Power: Creating Images, Creating Identities. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

MUJKIC, Asim, 2007, “We, the citizens of Ethnopolis”, Constellations – An International Journal of Critical & Democratic Theory, 4 (1): 112-128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.2007.00425.x.

DOI : 10.1111/j.1467-8675.2007.00425.x

NASH, Dennison, 1981, “Tourism as an anthropological subject”, Current Anthropology, 22: 461-481. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/2742284 (last consulted January 2025).

NASH, Dennison, and Valene SMITH, 1991, “Anthropology and tourism”, Annals of Tourism Research, 18 (1): 12-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(91)90036-B.

DOI : 10.1016/0160-7383(91)90036-B

NOY, Chaim, 2004, “This trip really changed me: backpackers’ narratives of self-change”, Annals of Tourism Research, 31 (1): 78-102. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.004.

DOI : 10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.004

OSBORNE, Peter, 2000, Travelling Light: Photography, Travel, and Visual Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

PICARD, David, 2002, “The tourist as social fact”, in Graham Dann (ed.), Tourism as Metaphor of the Social World. Wallingford: Cabi Publishing, 120-133. Available at https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20023098355 (last consulted January 2025).

ROBERTSON, Roland, 1995, “Glocalization: time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity”, in Mike Featherstone, Scott Lash, and Roland Robertson (eds.), Global Modernities. London: Sage Publications, 25-44.

SALAZAR, Noel B., 2005, “Tourism and glocalization: ‘local’ tour guiding”, Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (3): 628-646. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.012.

DOI : 10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.012

SANDIFORD, Peter J., and John AP, 1998, “The role of ethnographic techniques in tourism planning”, Journal of Travel Research, 37 (1): 1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759803700101.

DOI : 10.1177/004728759803700101

SATHER-WAGSTAFF, Joy, 2008, “Picturing experience a tourist-centered perspective on commemorative historical sites”, Tourist Studies, 8 (1): 77-103. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797608094931.

DOI : 10.1177/1468797608094931

SHELLER, Mimi, and John URRY, 2006, “The new mobilities paradigm”, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38 (2): 207-226. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1068/a37268.

DOI : 10.1068/a37268

SILBER, Laura, and Alan LITTLE, 1997, Yugoslavia Death of a Nation. New York: Penguin Books.

SKOLL, Geoffrey, and Maximiliano KORSTANJE, 2014, “Urban heritage, gentrification, and tourism in Riverwest and El Abasto”, Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9 (4): 349-359. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2014.890624.

DOI : 10.1080/1743873X.2014.890624

SMITH, Valene, 1989, Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

DOI : 10.9783/9780812208016

SMITH, Valene, 1998, “War and tourism: an American ethnography”, Annals of Tourism Research, 25 (1): 202-227. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00086-8.

DOI : 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)00086-8

STONE, Philip, and Richard SHARPLEY, 2008, “Consuming dark tourism: a thanatological perspective”, Annals of Tourism Research, 35 (2): 574-595. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.003.

DOI : 10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.003

TESTER, Keith, 1994, The Flâneur. London: Routledge.

UGRESIC, Dubravka, 2002, The Museum of Unconditional Surrender. Amesterdam: New Directions Publishing Corporation.

URRY, James, 2002, The Tourist Gaze. London: Sage Publications.

VOLČIĆ, Zala, 2007, “Yugo-nostalgia: cultural memory and media in the former Yugoslavia”, Critical Studies in Media Communication, 24 (1): 21-38. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180701214496.

DOI : 10.1080/07393180701214496

WEARING, Stephen, and Betsy WEARING, 2001, “Conceptualising the selves of tourism”, Leisure Studies, 20 (2): 143-159. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360110051631.

DOI : 10.1080/02614360110051631

No comments:

Post a Comment